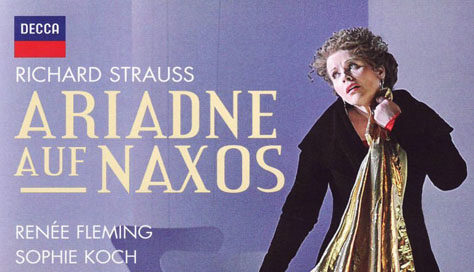

A Great Ariadne auf Naxos

Jason Victor Serinus, San Francisco Classical Review

At the end of Christian Thielemann’s live Staatskapelle Dresden DVD of Richard Strauss’ opera, Ariadne auf Naxos, recorded February 2012, all artifice falls away. The intentionally vaudevillian exaggeration that marked every gesture and phrase of Philippe Arlaud and Brian Large’s Prologue and initial scenes vanishes, replaced by some of most glorious, steady, and soaring Straussian conducting, playing, and vocal artistry of our era.

Heldentenor Robert Dean Smith (The tenor/Bacchus), initially a bit over-parted, rises to the occasion, his confident, smiling countenance and energized torso emitting line after line of sterling tone, with only the highest notes pinched. The woman whose heart he has won, the superb soprano Renée Fleming (Ariadne), sings as beautifully as she looks, pouring out long, intelligently shaped Straussian lines like few modern singers can. Her voice may be modest in size, but she gives 100 percent, and sounds perfect on DVD. As love triumphs over tragedy, and the lovers ascend blue pastel steps toward the moonlight, Thielemann’s orchestra swells as if in one long glorious outbreath.

At this moment, all the silliness of high soprano Jane Archibald (Zerbinetta) and her merry band fades into nothingness. To the flowery words of Strauss’ great collaborator, librettist Hugo von Hoffmansthal, we enter the exalted realm of supreme romance. Here we experience Strauss’ breath-robbing, tear-inducing faith in the ultimate triumph of romantic love, a faith that somehow survived the horrors of World War II to bloom one final time, over 30 years later, in his great Four Last Songs.

Before this comes a very different presentation. In the Prologue, mezzo-soprano Sophie Koch (the Composer) plays each line and gesture to the hilt. Her pronouncements and perfect high notes grow more and more passionate as everyone around her, most notably the revered tenor René Kollo (speaking the role of the Major-domo), Eike Wilm Schulte (The Music Master), and the lithe Christian Baumgärtel (the Dancing Master), does everything in their power to frustrate the composer and subvert his wishes.

The Prologue’s slapstick and burlesque-like elements continue with the arrival of Archibald’s Zerbinetta. Bedecked in a pink tutu and black hairdo straight out of the Weimar Republic, she is joined by her sidekicks, the fabulous Nikolay Borchev (Harlequin), Kenneth Roberson (Scaramouche), Steven Humes (Truffaldino), and Kevin Conners (Brighella). The men wear horizontal striped shirts and bright blue pants, and mug as though Laurel and Hardy were still with us.

There are delightful interactions with a ballet bar, bright shoes, hats, and other colorful props that reinforce the color-saturated nature of Strauss’ score. Everyone sings and mugs wonderfully, with Archibald reaching her peak in Zerbinettta’s delightful, impossibly long and high showpiece, “Großmächtige Prinzessin” (High and mighty princess). Her trill may be modest, and her final, ridiculously high climax a little shorter than one would wish, but her impeccable coloratura in her tour de force justifiably brings down the house.

Fleming, too, initially pours it on, her great aria “Es gibt ein Reich” (There is a realm) notable as much for her stresses on every vowel and consonant in the book as for her beautiful voice. Also mugging at first are her three wonderful cohorts, Christina Landshamer (Naiad), Rachel Frenkel (Dryad), and Lenneke Ruiten (Echo). But then, amidst more marvelously inventive staging, everyone settles down, sumptuous melodies emerge, and love has its final triumph.

I had initially planned to perform comparisons with some of the great dream conductor/cast Ariadne DVDs of the late 20th century. These include, most notably, Böhm’s 1994 Vienna Philharmonic performance (Janowitz, a much younger Kollo, Schmidt, Berry, Gruberova, and Zednik) and Levine’s great 1988 Metropolitan Opera line-up (Norman, Battle, Troyanos, King, and Nentwig). Also on the agenda was a 1969 Leinsdorf/BSO concert performance of the original 1912 version of the opera, with Sills sailing through an even longer, more impossible version of Zerbinetta’s aria that was soon trimmed a bit because of its difficulty.

But once the curtain closed on Thielemann’s outing, there was no reason to do so. His performance doesn’t just hold its own; it belongs in every opera lover’s collection. This is, on every level, a great production and performance.